|

| July 16, 2019 | Volume 15 Issue 27 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

50 Years Ago: Apollo 11 passes countdown test, national goal nears fulfillment

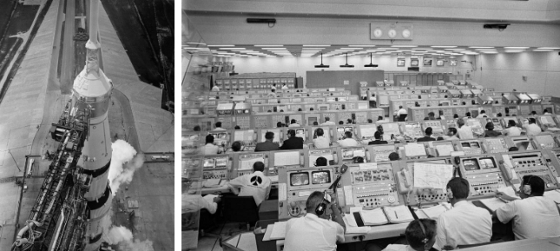

Left: Vapor emanating from the Saturn V rocket during the wet phase of the Apollo 11 Countdown Demonstration Test. Right: Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Center during the Apollo 11 CDDT.

By John Uri, NASA Johnson Space Center

[Countdown Series: 50th anniversary of Apollo 11]

The major activity at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) the first week of July 1969 was the Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT) for the Apollo 11 Moon landing mission. The CDDT, a full dress rehearsal for the actual countdown to launch, consisted of two parts. The "wet" test included fueling the rocket as if for flight, with the countdown cutting off just prior to first-stage engine ignition, and did not involve the flight crew. This was followed by the "dry" test, an abbreviated countdown without fueling the rocket but with the flight crew boarding the Command Module (CM) as if on launch day.

The wet countdown was completed on July 2, and the dry test the next day, with astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin, and Michael Collins suiting up and climbing aboard their CM. Controllers in Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center (LCC) at Launch Complex 39 monitored all aspects of the CDDT as they would on launch day. The test was a complete success, clearing the way for the start of the actual countdown.

Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins suiting up in preparation for the CDDT.

Left: Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Aldrin, Collins, and Armstrong walk out from crew quarters to the Astrovan on their way to Launch Pad 39A for the CDDT. Right: In the White Room at Launch Pad 39A, the closeout crew prepare to close the hatch to the Apollo 11 CM during the CDDT.

Left: Apollo 11 astronauts (back to front) Collins, Armstrong, and Aldrin have exited the CM into the White Room at the conclusion of the CDDT. Right: Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins in the Astrovan after the conclusion of the CDDT.

On July 2, NASA announced that Armstrong and Aldrin would leave three symbolic items behind on the Moon to commemorate the historic first landing -- an American flag, a commemorative plaque, and a silicon disc bearing messages from world leaders. NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine created the Committee on Symbolic Activities for the First Lunar Landing and appointed Willis H. Shapley, NASA Associate Deputy Administrator, as its chair on Feb. 25, 1969.

After reviewing advice from the Smithsonian Institution, the Library of Congress, the Archivist of the United States, the NASA Historical Advisory Committee, the Space Council, and congressional committees, Shapley's committee recommended to Administrator Paine that these three items be flown. The astronauts would plant the 3-ft x 5-ft flag near their Lunar Module (LM) during their spacewalk. The stainless steel plaque bore the images of the two hemispheres of the Earth and this inscription:

Here men from the Planet Earth

first set foot upon the Moon

July 1969 A.D.

we came in peace for all mankind

The signatures of the three astronauts and President Richard M. Nixon also appeared on the plaque. Workers mounted it on the forward landing leg strut of the LM. The messages of goodwill from 73 world leaders were etched on the 1 1/2-in. silicon disc using the technique to make microcircuits for electronic equipment. The crew aimed to place the disc on the lunar surface at the end of their spacewalk.

The Lunar Flag Assembly.

Left: Stainless steel commemorative plaque. Right: Silicon disc containing messages of goodwill from world leaders.

During a July 5 press conference in the auditorium of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston, the Apollo 11 astronauts revealed the call signs for their spacecraft.

They named their CM Columbia and their LM Eagle. "We selected these as being representative of the flight, the nation's hope," said Armstrong. Columbia is a national symbol, standing atop the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The CM was also named in recognition of the spaceship in the 1865 Jules Verne novel "From the Earth to the Moon." The LM was named after the symbol of the United States, the bald eagle, featured on the Apollo 11 mission patch.

In a second event, the astronauts answered reporters' questions from inside a glass-enclosed conference room at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL). After their mission, the returning astronauts were quarantined in the LRL for 21 days to prevent any back contamination of the Earth by any possible lunar microorganisms. During that time, they held press conferences and other events in the glass-enclosed conference room.

Left: Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins holding a copy of the commemorative plaque they planned to leave behind on the Moon and their mission patch.

Halfway around the world, on July 2 the Apollo 11 Prime Recovery Ship USS Hornet (CVS-12) arrived at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, to begin provisioning for her historic assignment. Workers loaded a boilerplate Apollo capsule onto the aircraft carrier to be used for recovery practice. The NASA recovery team, the Frogmen swimmers from the US Navy's Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) who assisted with the recovery, and some media personnel arrived onboard. For the recovery operation, Capt. Carl J. Seiberlich adopted the motto Hornet Plus Three, indicating the goal of a safe recovery of the three astronauts returning from the Moon.

On July 3, Capt. Seiberlich introduced the 35-member NASA recovery team to the Hornet's crew. Donald E. Stullken, Chief of the Recovery Operations Branch at MSC, who led the NASA team was the inventor of the inflatable flotation collar attached by swimmers to the capsule after splashdown. His assistant John C. Stonesifer was responsible for decontamination and quarantine operations. Stullken and Stonesifer briefed Hornet's 90-man Command Module Retrieval Team on all events associated with the recovery and retrieval of an Apollo capsule and its crew.

Workers prepare to hoist a boilerplate Apollo CM aboard USS Hornet in Pearl Harbor. [Credit: US Navy Bob Fish]

Two MQFs arriving by barge to be loaded aboard the USS Hornet in Pearl Harbor. [Credit: US Navy]

On July 6, workers loaded two Mobile Quarantine Facilities (MQFs) aboard Hornet. One MQF was to house the returning astronauts, a flight surgeon, and an engineer from shortly after splashdown until their arrival at the LRL in Houston several days later. The second MQF was designated as a backup should there be a problem with the first or if quarantine protocols were violated at any time requiring additional personnel to be isolated. Along with the MQFs, Navy personnel loaded other equipment necessary for the recovery, including 55 one-gallon containers of sodium hypochlorite to be used as a disinfectant.

In case Apollo 11 were not successful in accomplishing the first Moon landing, NASA continued preparations to support an Apollo 12 mission as early as September 1969.

On July 1, workers in KSC's Vehicle Assembly Building stacked the spacecraft atop its Saturn V rocket.

Left: Apollo 12 spacecraft arriving at the VAB. Right: Apollo 12 spacecraft being lowered onto the Saturn V rocket in the VAB.

Almost there ...

July 1969: Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin, and Michael Collins were ready to embark on their historic journey to fulfill President John F. Kennedy's goal to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth. Arriving at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) after the Fourth of July holiday weekend, they busied themselves with final training for the mission. All three piloted aerobatic flights aboard T-38 Talon training aircraft, spent time reviewing their flight plan, Armstrong and Aldrin trained in the Lunar Module (LM) simulator while Collins did the same in the Command Module (CM) simulator, Aldrin experienced one-sixth gravity during KC-135 parabolic flights, and Armstrong flew helicopters to hone his skills for piloting the LM to the lunar surface.

Two days before launch, the trio held a brief news conference, with reporters asking any final questions via a television link up -- NASA wanted to minimize the astronauts' exposure to people to prevent any illnesses that might delay the mission or cause any problems during the flight. The preliminary countdown for launch began on July 11 and the terminal countdown three days later.

Four days before launch, Apollo 11 astronauts (left to right) Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins arrive for work at KSC for some of their final simulator runs.

Left: Armstrong and Aldrin conduct a simulation in the LM simulator. Middle: Aldrin during a 1/6-g KC-135 training session. Right: Collins exiting a T-38 aircraft after completing an aerobatic training flight.

Left: Apollo 11 Commander Armstrong arrives for helicopter training to sharpen his skills for the Moon landing. Right: Armstrong during an EVA training session, rehearsing his first step on the Moon.

Between July 7 and 9, the Apollo 11 prime recovery ship USS Hornet conducted nine Simulated Recovery Exercises (SIMEX) in local Hawaiian waters, with US Navy Frogmen as stand-ins for the astronauts wearing Biological Isolation Garments (BIG), before returning to Pearl Harbor. Once in port, the rest of the NASA personnel and press corps came aboard, as did the Frogmen who had been given a few days of shore leave.

On July 12, Hornet slipped her moorings and sailed from Pearl for her first on-duty station to support a possible launch abort. Should anything have gone wrong during the first hours of the mission, Apollo 11 would have made an emergency splashdown in the Pacific Ocean about 1,600 miles southwest of Hawaii. Hornet crossed the equator on July 15, with the usual onboard celebrations, arriving at the abort location about five hours before the Apollo 11 launch. Nine more SIMEXs were completed, including a challenging nighttime recovery exercise. Hornet remained at this duty station until Apollo 11 was safely on its way to the Moon, then headed north toward the nominal end of mission splashdown area about 1,200 miles southwest of Honolulu and 450 miles south of Johnston Island.

SIMEX operations with USS Hornet. Left: USS Hornet approaching the boilerplate Apollo CM as swimmers jump from the recovery helicopter. Middle: Swimmer being hoisted onto a recovery helicopter. Right: Swimmers drying their BIG suits on Hornet's deck.

NASA personnel aboard Hornet were rehearsing some of the activities associated with the quarantine of the crew after splashdown to prevent back contamination of Earth with any possible lunar micro-organisms. According to the plan, the designated decontamination swimmer, Lt. Clarence J. "Clancy" Hatleberg of Underwater Demolition Team-11 who in May had trained with the Apollo 11 astronauts in the Gulf of Mexico, would briefly open the CM hatch after splashdown and hand them their BIGs, which they donned while still in the capsule floating in the water.

Once the astronauts were out of the capsule and aboard a life raft, Hatleberg would decontaminate them and the capsule. A rescue helicopter then would hoist the astronauts aboard and fly them to the carrier. Sailors would take the helicopter below decks on an elevator, and the astronauts walked to and entered the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), where they remained, along with a flight surgeon and an engineer, until Hornet arrived in Hawaii. They were then to be flown back to Houston to continue their quarantine at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston.

The MQF was equipped with a decontamination lock to allow the transfer of lunar samples and film to the outside without breaking the biological barrier. During Hornet's cruise to the recovery zone, John K. Hirasaki, a systems engineer with MSC's Landing and Recovery Division, and Eugene G. Edmonds, Chief of the General Photographic Branch of the Office of Technical and Engineering Services, practiced the transfer of film canisters from inside the MQF.

Hirasaki first simulated the retrieval of film from a boilerplate CM that was attached to the MQF by a temporary tunnel to maintain biological isolation. Inside the MQF, he vacuum sealed the film in plastic bags and placed them in the lock, which he flooded with sodium hypochlorite solution, a disinfectant to kill any possible pathogens. He then drained the lock, and Edmonds retrieved them for packing into shipping containers. The process would be repeated on landing day, for the lunar samples as well as the film that the astronauts returned with from their mission.

NASA personnel rehearsing transfer of film canisters from inside the MQF aboard Hornet.

While preparations for the first Moon landing mission were reaching their conclusion, NASA continued to plan for a possible Apollo 12 mission in September, should the first landing not be successful. At KSC, the Saturn V for that mission was already stacked on its Mobile Launch Platform inside the Vehicle Assembly Building. At Ellington Air Force Base near MSC, Apollo 12 Commander Charles "Pete" Conrad completed five flights in the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV). Apollo commanders and their backups used the LLTV to simulate the flying characteristics of the LM during the last few hundred feet before touchdown.

Left: Apollo 12 Commander Conrad flying LLTV-2. Right: Conrad after completing a training flight aboard LLTV-2.

In an unusual episode of warm relations between the two superpowers still very much in competition for dominance in space, Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman was invited by the Union of Soviet Societies of Friendship and the Institute of Soviet-American Relations to tour Russia. Borman and his wife Susan arrived in Moscow on July 2 for an eight-day visit. They were greeted at Sheremetievo Airport by Soviet cosmonauts Georgy T. Beregovoi, Gherman S. Titov, and Konstantin P. Feoktistov, and General Nikolai P. Kamanin, Director of the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City.

Borman became the first American astronaut to visit Star City on July 5, where he met with officials and many Soviet cosmonauts. He also met with Academician Mstislav V. Keldysh, President of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and one of the founders of the Soviet space program. That meeting would prove useful just a few days later.

Goodwill gestures notwithstanding, the Soviet Union was still very much in the race to land humans on the Moon. In late June, workers at the Baykonur Cosmodrome rolled out an N-1 Moon rocket to its launch pad. With a mockup N-1 rocket on the adjacent pad for fit checks, for a few days the scene at Baykonur was impressive as two Moon rockets stood side by side. Atop the "live" rocket was a modified Soyuz spacecraft the Soviets intended to send on an unpiloted lunar orbital mission.

On July 3, the 30 engines of the rocket's first stage ignited, lighting up the midnight sky at Baykonur. For the first 10 seconds of the launch, everything appeared to be nominal, but at an altitude of 100 meters, the rocket seemed to stall and began tilting to one side. The Launch Escape System's engines fired, pulling the spacecraft's descent module to safety but the giant rocket fell back onto its launch pad, exploding in a tremendous fireball.

The failure was later attributed to a small explosion in one of the first stage's 30 engines that rapidly engulfed multiple nearby engines. The launch pad was destroyed, the damage so severe it was readily apparent on American surveillance satellite imagery. The accident, the second following the first launch failure in February 1969, set the N-1 program back by about two years.

Left: Two N-1 Moon rockets on adjacent pads at Baykonur. Middle: The Launch Escape System fired to pull the lunar spacecraft free of the now-falling N-1 rocket. Right: Reconnaissance satellite image of the two N-1 launch pads at Baykonur, with the right-hand pad showing the damage from the July 3 explosion. [Credits: National Photographic Interpretation Center, RKK Energiya]

Undeterred by the N-1 explosion, the Soviets made one more attempt to upstage Apollo 11 -- a robotic lunar sample return mission. On July 13, they launched Luna 15 toward the Moon on a Proton rocket -- a previous attempt in June ended in a launch failure. Four days later, as Apollo 11 was headed toward the Moon, Luna 15 entered an elliptical lunar orbit. Concerns at NASA that Luna 15 would interfere with the Apollo 11 mission were allayed when Borman contacted Academician Keldysh (the two had met in Moscow just a few days before) who provided Luna 15's planned trajectory to NASA, the first such exchange in Soviet-American space relations.

Initially planned for a July 20 landing, Soviet controllers concerned about the ruggedness of the planned landing site in the Mare Crisium kept Luna 15 in orbit an extra day. Finally, on July 21 after 52 orbits around the Moon, Luna 15 began its descent toward the surface. By this time, Armstrong and Aldrin had already completed their walk on the Moon and were preparing to lift off to rejoin Collins in lunar orbit. But transmissions with Luna 15 ceased early, and it is estimated that it crashed at excessive speed -- apparently its attitude at the time the descent engine fired was off by several degrees. In September 1970, Luna 16 completed its predecessor's mission by returning lunar soil samples from the Mare Fecunditatis.

Left: Mockup of what Luna-15 would have looked like after a soft landing on the Moon (the brown sphere at the top of the spacecraft is the return capsule). Right: Relative locations of the Apollo 11 and Luna 15 landing sites. [Credits: RKK Energiya]

Published July 2019

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy